The lives they left behind: Suitcases from a State Hospital Attic

Peter Stastny and Darby Penney

written by Rose

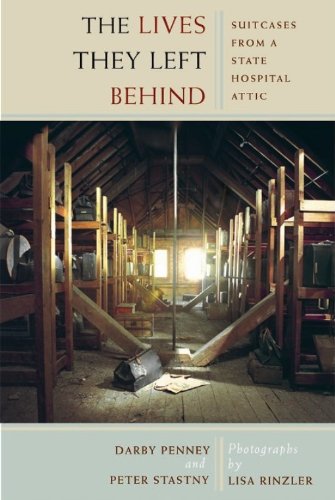

Clues to the personalities of the people who had packed the suitcases, the objects that left an indication to their identity, are sealed inside in darkness. While the cases were stranded in the stillness of the attic, the years gathered speed, like a racing driver with his foot hard on the accelerator. New York City expanded, architects shaped grand skyscrapers, rundown buildings were demolished to make room for modern structures and new developments. New parks were created, and shopping centres erected. Cars surged down freeways engines roaring as societal shifts began in earnest. The monolithic stigma towards mental health patients was progressively moving to a change in attitude and treatment.

Clues to the personalities of the people who had packed the suitcases, the objects that left an indication to their identity, are sealed inside in darkness. While the cases were stranded in the stillness of the attic, the years gathered speed, like a racing driver with his foot hard on the accelerator. New York City expanded, architects shaped grand skyscrapers, rundown buildings were demolished to make room for modern structures and new developments. New parks were created, and shopping centres erected. Cars surged down freeways engines roaring as societal shifts began in earnest. The monolithic stigma towards mental health patients was progressively moving to a change in attitude and treatment.

Yet, in the clinical wards of Willard hospital, many patients never saw the rapidly evolving landscape of the Metropolis. Some of them featured in the exhibition were institutionalised for decades. History and time were trapped inside the trunks and cases. In one case, a photograph of a beautiful dark-haired girl in an elegant dress edged with lace. She was born in Paris and had studied at the Sorbonne. She was estranged from her parents, who later refused to accept her back into the home. You imagine her dancing in grand halls, with suitors fighting for her attention. She has a kind face, a slight smile playing on her lipts, there is a light in her eyes, a yearning expression lingers on her face. Anyone looking at the photograph would envision her having a pleasing future. Yet photographs can be deceptive, we become skilful actors in front of the lens. Musty books on music, history and philosophy are found tucked into her case with clothes. Madeline became interested in mysticism, the occult and telepathy, it would be her downfall. She would never see her parents again. What happens to girls who have no family to help when times get difficult in a big city? It puts them in a more dangerous and vulnerable situation. They have no one there to speak up for them when placed in insitutions. The one thing you think of when reading her and other stories is ‘They should have been loved by someone.’

The authors ask a profound question. ‘Did her mental health diagnosis justify the fact that she was institutionalised without appropriate therapy for 48 years?’ In another case, an African American’s army uniform is folded with care. Photographs show him smiling, we know he liked ladies with bright smiles, yet he was lost and lonely when admitted to hospital. A delicate baby shoe lay with his clothes, the tiny shoe whispered its own frail tune of the sensitive soul that once held it in his hands. He treasured it. The little shoe was like a gentle melody, that raced through the passage of time to a new generation and society, where people stood reading his story in an exhibition about mental health.

In 1995 a curator for the museum of New York State arrived to see if anything could be salvaged from Willard hospital. He was ordered to bring ten suitcases back and leave the rest. Possibly, these forgotten lives spoke to him at that moment, perhaps he heard the faint murmur of their tragic narratives in that attic where the past was held captive. He defied the instruction and took all the suitcases. He, like the authors, wanted to help the forgotten speak. Despite injustices they could not change, the curator and authors could give the invisible a voice, could make sure that their existence became something more than an tragedy. The stories of the patients would reach thousands of people and raise the debate about mental health in society in an exhibition. The authors moved these personal stories of patients into the world and society and they also discuss the way mental health is managed in the modern society.

Did the holder of the suitcases clutch the handle tightly as they entered this building? Were they nervous? Did any argue as they passed through the hospital doors? The authors tell us that one protested later. It’s on her records. Did they know they were never going to see that suitcase again? It’s a poignant tragic story that won’t fail to touch a reader’s heart, and yet it is also a positive story; the authors respected these lives and considered how to put their stories into the exhibition, they carefully researched and provide the reader with as much evidence as they can. The fact that the exhibition was seen by so many people really adds a transforming element to the story. This is not just an exhibition about injustices and lost lives, though that is a great part of the story, it’s also about the effect the stories will have on other people reading the stories and teaching others about the history of mental health and institutions. If one can learn from the past, one can try and make sure it never happens again.

It is a fascinating read for anyone interested in the history of mental health, psychology, eugenics or history. The authors discuss the complex reasons that some patients were admitted to Willard. Unfortunately, in earlier times, people could be placed to a mental hospital for breaking society’s so-called ‘moral codes’. This included a person’s sexuality, such as being gay which was unjustly and shockingly treated as a mental illness in the past. There were other moral codes that could be considered a reason for admittance into a mental hospital or asylum. Females were expected to behave in a certain manner in society. If they acted differently or crossed the boundaries of what was expected, they could be sent to a mental hospital to be ‘cured’.

It is a fascinating read for anyone interested in the history of mental health, psychology, eugenics or history. The authors discuss the complex reasons that some patients were admitted to Willard. Unfortunately, in earlier times, people could be placed to a mental hospital for breaking society’s so-called ‘moral codes’. This included a person’s sexuality, such as being gay which was unjustly and shockingly treated as a mental illness in the past. There were other moral codes that could be considered a reason for admittance into a mental hospital or asylum. Females were expected to behave in a certain manner in society. If they acted differently or crossed the boundaries of what was expected, they could be sent to a mental hospital to be ‘cured’.

In the stories featured in the book, many of the patients were diagnosed with paranoid thoughts, delusions or schizophrenia and similar conditions. At that time, anyone hearing voices could easily be categorised as ‘crazy’. In some tragic cases, the patients may have begun life with an early tragedy in childhood, that may have caused depression or created a huge change in circumstances, that through no fault of their own, escalated and followed them through life, making them more vulnerable and susceptible to stress and depression in society.

For instance, the authors describe one lady that had lost her mother as a little girl, this traumatic life event had created a great deal of trauma, ultimately leading to more tragic life events and illness. Sadly, this book allows the reader to see that sometimes, it’s simply a case of back luck. People were institutionalised due to life dealing them a terrible emotional blow, that could lead to a mental breakdown. The problem was, it was easy to be admitted and put to work in a mental hospital, but it was very difficult for some patients, who the doctors believed could never function in society to get out. There is no doubt that some patients even with proper care and therapy may have found it impossible to be integrated back into society. Yet, the authors provide compelling evidence that some were kept without proper therapy and for far too long.

Eugenics was popular in the medical profession at the time these patients were assessed. This worked against the institutionalised, as those deemed ‘mad’ according to the teachings of eugenics, were often treated like they had a disease other people could catch. Professionals felt they should be kept apart from ‘normal’ people in society. Willard was about four and a half hours from New York, where some patients had lived. There was very little opportunity to escape as the institution was in the middle of nowhere. Eugenics also fostered the belief that the mentally ill should be prevented having children, as their ‘defective’ genes could be passed down to the next generation. Eugenics was also the reason that some females considered crazy or with limited intelligence were sterilised, preventing them from having any children.

Many patients in the stories were found in poverty and were unable at that time to be financially independent. Some had been prosperous but had fallen on hard times. Some were institutionalised by their families. Others were grieving and suffering from the death of a loved one. Poverty is a strong theme in the book and in the patient’s stories, including the way that patients were treated once admitted. The authors discuss evidence that that indicates a patients treatment varied according to the financial situation of that patient once admitted. The effect of poverty on mental health is a subject that arises again and again with the personal life histories. Even modern research shows that people living in poorer areas and suffering from poverty are more suspectable to stress. This may sound obvious, but the impact of this stress can impact a person’s heath in debilitating ways. Significantly, if patients were found in a distressing state, one wonders, could their situation have been different with treatment in another month.

The main questions the authors ask are ‘Why were some patients kept without proper therapy for decades?’ and ‘Why were some not given the opportunity to be integrated into society again?’

To understand these complex questions the authors Stastny and Penney researched the history of the hospital, societal attitudes of the time, eugenics and its impact on medical decision making, therapy and the way doctors practised psychotherapy during the period the patients were admitted. They also discuss the way that mental hospitals functioned as self-sufficient places, where patients put to work very quickly. They detail the positive and negative aspects of patients with mental health problems being forced into work. The authors describe one man worked as a gravedigger until very old age, he seemed to use this to negotiate to have some private time and making his life more bearable. Despite this, because he worked so consistently and did jobs other men working at the hospital disliked, the doctors seemed to have been lax in reassessing his actual need to be in the hospital. Others, like the French girl I talked about earlier, fared far worse, and it’s obvious she asked about her freedom all throughout the long years at the hospital.

If one can picture such an institution, if you were quiet, accepted the doctors and nurses’ orders, you appear to be considered ‘well behaved’ if you argued your position you were considered ‘volatile’ or ‘augmentative’ and ‘disruptive’. Authority in the mental hospital and power relations are a constant theme. The medical staff had all the power, the vulnerable patients none. The patients also had no one to defend their individual case or someone to speak on their behalf. It seems that anyone that disagreed or argued their case for freedom, or different medical intervention was labelled a ‘troublemaker’ by medical staff. Many were prescribed heavy drugs that would later cause physical disabilities.

While telling the patients stories, one weakness which the authors readily admit is the fact that the patients were not there to speak for themselves. We cannot hear their testimonies or stories written or oral narratives. The full medical records of patients are legally restricted, even if used, the name must be anonymous. Despite this limitation, the authors provide brief notes written by some of the doctors. Though short, they are very revealing, telling us something about the lack of power the patient had in the hospital. Those decisions about their lives were made by one doctor, a man that may have been biased against some patients and certain conditions. The attitudes and personalities of the doctors in these medical notes give the reader an insight into how the patients were perceived by doctors. These parts of the book are a harrowing read. The authors provide a brief biography of the patients featured in the exhibition and the stories are both moving and compelling. However, we do not have the whole story, some background information from the patients is missing, there are lingering questions: Why did Madeline’s family refuse to have her back home in Paris? Why was she estranged from them? One wonders about the upbringing and their childhood experiences. We will never have the whole story, but the authors provide as much research as they can, and each story is fascinating in its own way.

The authors leave us debating the way patients were diagnosed through the decades, discussing how diagnoses were made, and the type of diagnoses that were frequent during this time. They discuss the history of institutionalised care and debate whether care in the modern world is any better. Their answer might surprise and shock some people. The authors have done more than write a book about a group of people that did not have the opportunity to live a life. The authors helped create an exhibition to give these forgotten voices a voice. They took these stories and impacted society and others with the narratives. They strove to teach people about mental health in the past and create intellectual debate about the historical impact of mental health care in the present day. Though traumatic reading at times, it’s remarkable that we have these stories, and that we can learn from them. I highly recommend this book.