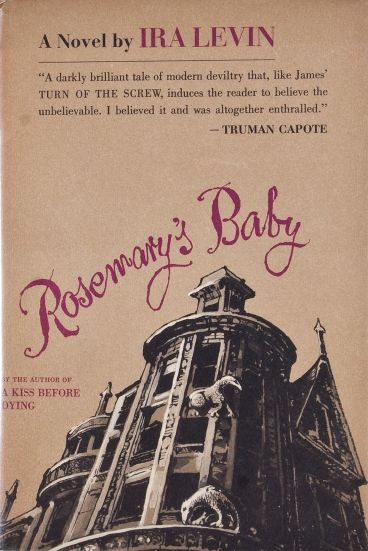

Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin

The year is 1967: a time where artists and musicians in the United States flourished but dangerous cults like the Manson family were emerging. Jim Jones predicted the end of the world; women fought for their rights, and in the Vietnam battle of Đắk Tô, up to 1,800 casualites were reported in a ferocious battle. In this year Dr James Bedford became the first person to be cryogenically preserved. It was a time for new ideas to be experimented, and a time where some took advantage of the freedom available in society. It was during this chaotic time that Ira Levin’s second novel, Rosemary’s Baby, was released. In the introduction of the latest edition Chuck Palahniuk discusses how Levin brought a new type of horror to the audience, rather than horror set in foreign places, highway motels or haunted houses. Levin moved the horror closer, into the home. Palahniuk states that in Rosemary’s baby, everyone is the enemy; this is what produces a claustrophobic atmosphere that amplifies as you turn the pages. The elderly neighbours are Satanists and the man Rosemary lays next to every night is willing to sacrifice anything to become a Star. The horror looks ordinary: it’s dressed conventionally and hidden in our society. Levin appears to say ‘anyone is capable of evil’. Rosemary is allowed no control, even over her own body or mind. This authoritarian oppression electrifies the fear. Levin understands terror; that a complete loss of control is terrifying. Rosemary’s baby was the most popular horror novel of the sixties, Truman Capote rated the novel highly and willingly wrote his praise, this empowered Levin’s novel to receive attention.

The year is 1967: a time where artists and musicians in the United States flourished but dangerous cults like the Manson family were emerging. Jim Jones predicted the end of the world; women fought for their rights, and in the Vietnam battle of Đắk Tô, up to 1,800 casualites were reported in a ferocious battle. In this year Dr James Bedford became the first person to be cryogenically preserved. It was a time for new ideas to be experimented, and a time where some took advantage of the freedom available in society. It was during this chaotic time that Ira Levin’s second novel, Rosemary’s Baby, was released. In the introduction of the latest edition Chuck Palahniuk discusses how Levin brought a new type of horror to the audience, rather than horror set in foreign places, highway motels or haunted houses. Levin moved the horror closer, into the home. Palahniuk states that in Rosemary’s baby, everyone is the enemy; this is what produces a claustrophobic atmosphere that amplifies as you turn the pages. The elderly neighbours are Satanists and the man Rosemary lays next to every night is willing to sacrifice anything to become a Star. The horror looks ordinary: it’s dressed conventionally and hidden in our society. Levin appears to say ‘anyone is capable of evil’. Rosemary is allowed no control, even over her own body or mind. This authoritarian oppression electrifies the fear. Levin understands terror; that a complete loss of control is terrifying. Rosemary’s baby was the most popular horror novel of the sixties, Truman Capote rated the novel highly and willingly wrote his praise, this empowered Levin’s novel to receive attention.

It’s the formidable darkness that lies behind this false veil of commonplace that chills the reader, ramping up the suspense and paranoid atmosphere, which validates Levin’s talent. He places, Rosemary and Guy devoted, planning their first home and baby: a young couple in love at their happiest point, a time of dreams and planning, setting up home and being in love. Just as Levin has you comfortable, he poses a terrible question. What if the man Rosemary loves is not a good man at all. What if he is capable of hurting her in the most horrific way imaginable?

This is another masterful technique of Levin; he understands that the idea of not trusting the person you live with is something human beings would find incredibly scary. He’s not placing the horror in the hands of a madman with a knife, or a stranger breaking into the apartment. He is putting the horror right next to Rosemary in a person she loves.

Levin was trained in play writing, his preferred form of writing; this may have shaped his style: minimalist, reductive, stripped of the ornate, yet ingenious in its pure simplicity. The fast way Rosemary’s Baby draws you in is skilled writing. In Rosemary, Levin creates the ultimate innocent victim, far from family, naïve, gentle and kind, the reader wants her to be safe. She is a reminder of young dreams and innocence; she is creating a haven of domesticity and love.

A theme in Rosemary’s Baby is autonomy over one’s own body, and decisions about our bodies: in this case the female body. In the book, as in the film, Rosemary has little control over her own body. Decisions about her pregnancy are left to other people, to outsiders or her husband. She is persuaded away from the doctor she chose, she cannot choose vitamins, she’s forced to take health drinks, not knowing what is in them. During the night she becomes pregnant, she wakes covered in deep scratches, Guy states he had sex with her while she slept, that he became overzealous. It’s as if this is acceptable, as he is Rosemary’s husband. That rape is somehow standard in these circumstances, because she is owned by him; Guy acts as if she is something he owns, rather than an equal partner, with equal rights.

Again, Rosemary had no control over her own body, as she was completely drugged and at the mercy of other people. The lack of control over your own wishes and your body is abhorrent to the reader and Levin knows it. In the 1960s some states were fighting for the right for abortions and to make their own choices over their bodies, to allow raped women to have abortions. So this would have been discussed in the news during the sixties. To think of someone making decisions about our bodies is a terrifying thought.

When Rosemary experiences physical pain for weeks, she’s denied information from the doctor. In fact, information is withheld from her throughout the film by other adults. This puts in her a vulnerable situation, much like a child. The people close to Rosemary become bullying authoritarians and for a long time Rosemary submits, despite not liking it. We have to ask ourselves why? It becomes more and more uncomfortable for the reader to witness this emotional abuse in the novel. It’s the same in the film; the viewer becomes deeply frustrated by Rosemary’s powerlessness and inability to stand up for herself. We are reading thinking ‘Rosemary do something.’

But this is precisely what Levin wanted. The heroine is not rebelling for her rights at first; she’s simply accepting the abuse, Levin knows this makes the reader feel exasperated, and it creates a very claustrophobic atmosphere. Levin may also have been implying something about gender roles and society at the time in the 1960s. This was a time when housewives were still fighting for some basic rights in the home. Rosemary grew up in a household where she was expected to follow strict religious rules. We are told she was taught by nuns, who would become abusive if she did not submit to their instructions. Rosemary has been taught to be a good polite Catholic girl.

The stark personality differences between Rosemary and her husband are evident throughout the chapters; Rosemary is kind, caring and gentle. Guy is confident selfish, narcissistic and willing to sacrifice anyone and anything in order to become a famous actor. The female gender is viewed as less ‘important’ than the male. Yet it is the female who is having the baby. There are strong gender statements made throughout the novel. With the Castevet’s we see that Levin has placed some humour in the novel, they are grotesque people, Minnie Castavet is bad mannered vulgar and crosses all boundaries, this is contrasted with Rosemary’s quiet dignified personality. Having the Satanists as gaudy repulsive characters crafts humour; we are both disgusted by them and amused by their appearance it gives a comic element to the scenes. The fact they are elderly is another key factor in Levin’s creation of trust. Wouldn’t a young woman be more likely to trust an elderly couple at her door?

The stark personality differences between Rosemary and her husband are evident throughout the chapters; Rosemary is kind, caring and gentle. Guy is confident selfish, narcissistic and willing to sacrifice anyone and anything in order to become a famous actor. The female gender is viewed as less ‘important’ than the male. Yet it is the female who is having the baby. There are strong gender statements made throughout the novel. With the Castevet’s we see that Levin has placed some humour in the novel, they are grotesque people, Minnie Castavet is bad mannered vulgar and crosses all boundaries, this is contrasted with Rosemary’s quiet dignified personality. Having the Satanists as gaudy repulsive characters crafts humour; we are both disgusted by them and amused by their appearance it gives a comic element to the scenes. The fact they are elderly is another key factor in Levin’s creation of trust. Wouldn’t a young woman be more likely to trust an elderly couple at her door?

Palahniuk states that Rosemary’s baby is political. That in the novel the institution of God and religion is torn down, making a political statement. In one scene the Pope is visiting America and the only person being respectful towards God, is Rosemary. She is ridiculed. Rosemary was brought up a Catholic, and although she is no longer practising, she has natural respectful feelings towards God and religion. However, even a person non-religious would most likely show some respect.

The Castavet’s on the other hand are not able to be polite; they continually minimise the Catholic religion and ridicule its traditions. It’s clear from the very early meetings that they do not respect the religion nor do they have any respect for God. In the film by Polanski, he has Rosemary reading a magazine, on the cover is the question ‘Is God Dead?’ There are many ways to look at the way religion is treated in the book. One was the cultural time of the 1960’s. Society was becoming more complex. There were sectors of society that fought against traditional religious ideas, the sixties was a time of change, of challenging concepts.

In the 1960’s Anton Le Vey formed the first Satanist Church, which encouraged individualism and a focus on self, rather than a reliance on ‘outside’ religious institutions. However, unlike the witches in Rosemary’s baby who worship Satan, and who take objects and use their powers to blind and kill others, the Satanist church was against cruelty to others, towards children or animals. The idea that the Satanist church practised sacrifices was mere myth. Le Vey did not believe in worshipping Satan as a deity. Nor did he believe that Satan actually existed. The existence of the Satanist church is an extreme example of the many 1960’s social groups standing against long held religious beliefs. Many people were offering alternatives to the main stream religions, Levin would have been aware of this cultural change.

In the novel, Rosemary’s family have shunned her, as she married a protestant. Yet, she has something that no other character in the novel has; she has faith, faith in goodness and by the end of the film, this conviction is unmistakable, when she tells herself that she can save the baby. That the baby doesn’t have to become evil, that it is part of her.

Levin at the time he wrote said he imagined one of the scariest things to happen to a female was to have something growing inside them, knowing it wasn’t quite human. That this idea seemed to be one of the most terrifying he could imagine, and it was this idea that inspired his novel. So there are many way he sets fear in the novel, due to the novels small size, you can see that the types of fear he uses, have been carefully planned.

In the film, Polanski says that everything that happens in the film is realistic, it could have happened in real life. Polanski deliberately did not show the baby at the end of the film for this very reason. You only have a tiny glimpse of yellow inhuman eyes, eyes Rosemary saw in her dreams. It’s the same in the book, up to the point the baby is born and has physical differences; the rest of the novel is very realistic. For all the reader knows, these are insane people with strange beliefs in the devil, willing to hurt a female based on their belief system. During the rape Rosemary is hallucinating, so there is the possibility that she is imagining what she is seeing. However, at the end of the book when she sees the baby, she sees something inhuman. However, she states that the baby is still half hers, that evil could be overcome, again bringing the possibility that good could triumph over evil. Thus, there is a possibility that that her religious faith could salvage something.

In the film, Polanski says that everything that happens in the film is realistic, it could have happened in real life. Polanski deliberately did not show the baby at the end of the film for this very reason. You only have a tiny glimpse of yellow inhuman eyes, eyes Rosemary saw in her dreams. It’s the same in the book, up to the point the baby is born and has physical differences; the rest of the novel is very realistic. For all the reader knows, these are insane people with strange beliefs in the devil, willing to hurt a female based on their belief system. During the rape Rosemary is hallucinating, so there is the possibility that she is imagining what she is seeing. However, at the end of the book when she sees the baby, she sees something inhuman. However, she states that the baby is still half hers, that evil could be overcome, again bringing the possibility that good could triumph over evil. Thus, there is a possibility that that her religious faith could salvage something.

The power of Architecture used in Levin’s novel

The fictional Bramford was named by Levin after Bram Stoker who he admired. Early in the book we are told this is one of the most exclusive buildings in Manhattan and that apartments rarely become available.

The fictional Bramford was named by Levin after Bram Stoker who he admired. Early in the book we are told this is one of the most exclusive buildings in Manhattan and that apartments rarely become available.

The vision created of the Bramford is a gothic apartment building, majestic, powerful, regal and important housing the upper classes. The Bramford is a resilient character in the novel. It watches over all residents including Rosemary and Guy, it has the power to draw people to it, for people to desire to be under its roof. At one point in the novel Hutch says, perhaps it’s not the building itself, but possibly bad events that occurred in the building that draw immoral unsavoury people to it. The idea is put in the readers mind that due to some nasty events in history, the Bramford may attract a specific type of person and temperament to it.

Both Rosemary and Guy are warned away from the Building due to its unsavoury history. Hutch tells them about a murdered baby found in the basement and a practising Satanist lived there who claimed he’d conjured the devil. The history of the building builds its character; the Bramford is now viewed by the reader as potentially dangerous. Levin cleverly puts the thought in your mind ‘anything’ could happen in this place despite the wealth.

Yet in the minds of Rosemary and Guy it retains its majestic prestige and power. The Bramford is a status symbol. It’s the place that all young couples dream of living. The Bramford is a dream, and young couples look for dreams. They have goals they want to see materialise, they want to be part of this regal building and its wealthy clientele.

Using architecture in a fiction novel is not unusual. But the way that Levin chose his building, the affluent clients that live under the roof of the Branford, was unique. It’s one of the first times an apartment building was used as a setting for horror. The fact that it serves the elite, gives it the place a sense of safety, surely the upper classes are ‘normal’. And it is the very wealthy that Levin has as the Satanists, the upper echelons of society that have much power in society.

Even the girl that commits suicide at the beginning, and throws herself from the building is described as ‘street trash’ by the Castevets.’ She comes from an entirely different social class than the other residents and she is the one that dies.

Levin’s choice of architecture intensifies the atmosphere in the novel. Architecture is ingeniously and masterfully employed in the story, it’s also a magnificent character in the novel. It has presence. In Polanski’s film, he couldn’t have found a more suitable apartment building with the Dakota, it matches the vision the reader has of the building. Its power resonates in the film as a symbol of prosperity and authority. The way he films it at the beginning of the film, the angles giving it supremacy, it towers above Rosemary and Guy, they look so fragile below it.

There are many complex themes in Rosemary’s baby. Levin was not a prolific writer of novels, he wrote more plays and screenplays were his preferred interest. Rosemary’s baby is a short novel, yet that does not diminish its strength. The minimalist prose style that Levin used to tell the story, the way he strips away all unnecessary description, refuses to let his character’s ruminate for long, this stark, precise polished writing gives one the illusion when reading, over fifty years later, that this is a very contemporary novel. Yes, the ideas may be dated, Satan may have been a hotter topic in 1967, may have spurred the imagination of the reader at a disordered cultural time, but it’s difficult to imagine this novel being over fifty years old and that’s a testament to Levin’s skill. As someone who admires ornate descriptions and deep thinking characters, a literary style, I can also read Levin and admire his talent for creating immediacy, to generate such pure unembellished sentences, he restrains from adornments, which isn’t easy for a writer to do, and Levin’s scenes are intensely filmic. They were made for the screen.