Joe Orton – The Complete Plays

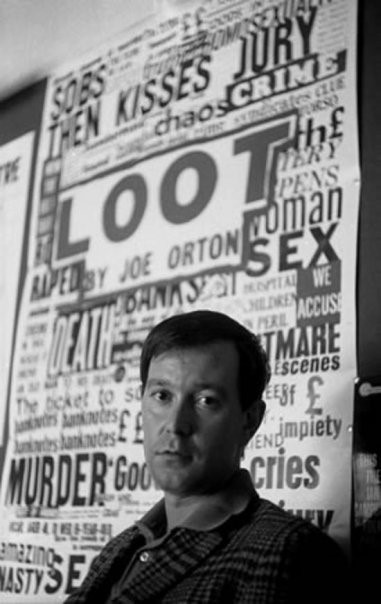

In the 1960s Joe Orton was interviewed by Eammon Andrews on television. On this programme one catches a glimpse of Orton’s dynamic personality. He has a mischievous boyish smile playing on his lips as he talks, he is charming, witty and intelligent. There is a disobedient spark in his eyes, a wildness of character that lives just under the surface of his words. In just minutes, the film camera has painted a striking image of a man considered one of the most ground-breaking playwrights of the 1960s. In the interview there is no evidence of the hardship of Orton’s youth, the deprivation he and his siblings suffered as children. Yet, if one looks closely at the dialogue of the disenfranchised characters in his plays, his personal fearlessness, the comical yet macabre scenes he presented to audiences. One can clearly see a personality shaped by difficult events in his childhood.

In the 1960s Joe Orton was interviewed by Eammon Andrews on television. On this programme one catches a glimpse of Orton’s dynamic personality. He has a mischievous boyish smile playing on his lips as he talks, he is charming, witty and intelligent. There is a disobedient spark in his eyes, a wildness of character that lives just under the surface of his words. In just minutes, the film camera has painted a striking image of a man considered one of the most ground-breaking playwrights of the 1960s. In the interview there is no evidence of the hardship of Orton’s youth, the deprivation he and his siblings suffered as children. Yet, if one looks closely at the dialogue of the disenfranchised characters in his plays, his personal fearlessness, the comical yet macabre scenes he presented to audiences. One can clearly see a personality shaped by difficult events in his childhood.

His work is also obviously influenced by the horrendous way gay men were treated in the 1950s and 1960s. Orton lived at a time in the UK when homosexuality was illegal. At this time, gay men were persecuted relentlessly in society and the government. By being forced to hide their sexuality, gay men were categorised as deviant and a negative influence on society and people in general. Orton like most men in this intolerable situation was forced to hide his sexual desires. His family had no idea that he was gay. The hypocrisy and stupidity of authoritarian figures, was one of Orton’s robust themes in his plays, especially in the play Loot.

Another prominent theme is the social classes in British society and social conventions. Orton was excavating from his individual life experiences and using them as catalysts in his plays. As Orton himself said, people can be bad, but they can also be tremendously funny in the way they conduct themselves in that badness. Orton’s vision of humanity could be sombre, but it was also witty comical and entertaining in its complete preposterousness. Orton unleashed fierce energy at his typewriter, crafting words with precision. Yet, he was also willing to take a chisel and sculpt characters into fruition with brutality rarely seen in the theatre world, creating some of the most unusual comical marginalised characters ever seen in plays, and tearing at the very fabric of British convention. He used comedy was a way to avoid censorship; comedy was a great tool for discussing taboo subjects.

Another prominent theme is the social classes in British society and social conventions. Orton was excavating from his individual life experiences and using them as catalysts in his plays. As Orton himself said, people can be bad, but they can also be tremendously funny in the way they conduct themselves in that badness. Orton’s vision of humanity could be sombre, but it was also witty comical and entertaining in its complete preposterousness. Orton unleashed fierce energy at his typewriter, crafting words with precision. Yet, he was also willing to take a chisel and sculpt characters into fruition with brutality rarely seen in the theatre world, creating some of the most unusual comical marginalised characters ever seen in plays, and tearing at the very fabric of British convention. He used comedy was a way to avoid censorship; comedy was a great tool for discussing taboo subjects.

Famously named ‘the Oscar Wilde of Welfare Gentility’, Terrance Rattigan stated that Entertaining Mr Sloane was the best play he’d seen in 30 years. Others damned Orton’s ‘dirty plays’, claiming they did not belong in the West End.

Orton was the master of absurdity, crafting outrageous scandalous scenes that were both entertaining and macabre. In his writing, Orton also transformed the stereotypical image of the gay man of the 1960s often portrayed as overtly camp in society at the time. Orton was doing more than creating a play for theatre, he was making bold statements about society and attitudes. He enjoyed shocking people out of complacency, pushing audiences out of their familiar worlds with a hard kick. Critically acclaimed, Orton equally infuriated some spectators, some left the theatre, others booed at the actors. He considered such outrage a victory. It implied the audience had felt something at a visceral level. Creating shocking dialogues for his marginalised characters, Orton was using a powerful rhetorical device to create an argument about British society and convention. In theatre his words created characters: outside, those same words created debate. He wanted the discussion to move from the theatre space into the media and wider society. Recently, Ian McKellen and Stephen Fry have supported a statue for Orton in the media. The plays leave you with two questions. What would Orton have achieved later in life? And how would Orton’s plays have changed with time?

Orton was the master of absurdity, crafting outrageous scandalous scenes that were both entertaining and macabre. In his writing, Orton also transformed the stereotypical image of the gay man of the 1960s often portrayed as overtly camp in society at the time. Orton was doing more than creating a play for theatre, he was making bold statements about society and attitudes. He enjoyed shocking people out of complacency, pushing audiences out of their familiar worlds with a hard kick. Critically acclaimed, Orton equally infuriated some spectators, some left the theatre, others booed at the actors. He considered such outrage a victory. It implied the audience had felt something at a visceral level. Creating shocking dialogues for his marginalised characters, Orton was using a powerful rhetorical device to create an argument about British society and convention. In theatre his words created characters: outside, those same words created debate. He wanted the discussion to move from the theatre space into the media and wider society. Recently, Ian McKellen and Stephen Fry have supported a statue for Orton in the media. The plays leave you with two questions. What would Orton have achieved later in life? And how would Orton’s plays have changed with time?

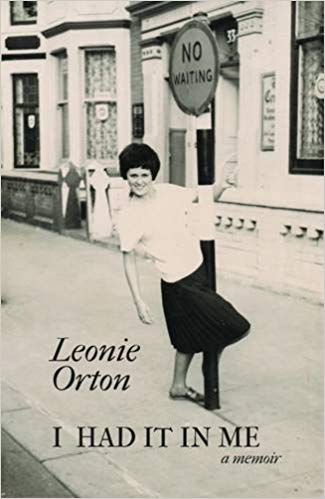

In an interview, Leonie Orton, Orton’s sister reveals that Orton had a much more complicated personality than his personal diaries revealed. Orton may have crafted the image of the bad boy playwright to a certain extent. It’s clear that he was rebellious, however many of his private experiences formed that defiant nature, including a fearlessness and the capacity to push boundaries to the furthest point possible without breaking the law. He may appear emotionally detached at times in his plays and his diary, but evidently, we can learn from Leonie that there was a gentler side to Orton. Psychologically, it is not unusual for people who have created an image for themselves for an audience and media to hide certain aspects of their more vulnerable traits. Leonie states that Orton was a very caring young man and the only person who’d ever really been kind to her. This statement demonstrates just what kind of brother Orton was. And Leonie has worked tirelessly with her sister to protect Orton’s name, and his estate, and to share Orton with the world by sharing her own experiences of him with others by giving talks and interviews.

In an interview, Leonie Orton, Orton’s sister reveals that Orton had a much more complicated personality than his personal diaries revealed. Orton may have crafted the image of the bad boy playwright to a certain extent. It’s clear that he was rebellious, however many of his private experiences formed that defiant nature, including a fearlessness and the capacity to push boundaries to the furthest point possible without breaking the law. He may appear emotionally detached at times in his plays and his diary, but evidently, we can learn from Leonie that there was a gentler side to Orton. Psychologically, it is not unusual for people who have created an image for themselves for an audience and media to hide certain aspects of their more vulnerable traits. Leonie states that Orton was a very caring young man and the only person who’d ever really been kind to her. This statement demonstrates just what kind of brother Orton was. And Leonie has worked tirelessly with her sister to protect Orton’s name, and his estate, and to share Orton with the world by sharing her own experiences of him with others by giving talks and interviews.

Orton was brought up in a working-class household on an estate in Leicester that his sister Leonie called ‘soulless’. In her memoir ‘I had it in me’ she gives us a unique insight into her brother. Leone describes his anger at the inequality of the social classes, how he and his siblings lived a very disadvantaged life on the council estate with the options of family members to eventually work in factories (Orton, Leonie, 2018). It’s a testament to Orton that he managed to take elocution lessons and eventually find a place at RADA. Orton’s mother was prone to infuriated outbursts, even in groups, that caused great embarrassment for the children. Sometimes they were shunned by other members of the community because of the actions of their mother. It does appear that Edith Orton was a bitter woman who loathed her low station in life, and who took her anger out on her children, especially her daughters. Though she did treat the boys better, they didn’t have a mother figure they could look up to. Orton’s father had no ambitions and earned very little, he is described as a totally submissive man and was not respected by either of his two sons. The harsh landscape of Orton’s early upbringing and his parents’ marriage which was from all accounts miserable, can be seen in his plays. But Orton also manages to turn some of the most terrible events into scenes of boundless humour, which was one his greatest gifts.

Orton was brought up in a working-class household on an estate in Leicester that his sister Leonie called ‘soulless’. In her memoir ‘I had it in me’ she gives us a unique insight into her brother. Leone describes his anger at the inequality of the social classes, how he and his siblings lived a very disadvantaged life on the council estate with the options of family members to eventually work in factories (Orton, Leonie, 2018). It’s a testament to Orton that he managed to take elocution lessons and eventually find a place at RADA. Orton’s mother was prone to infuriated outbursts, even in groups, that caused great embarrassment for the children. Sometimes they were shunned by other members of the community because of the actions of their mother. It does appear that Edith Orton was a bitter woman who loathed her low station in life, and who took her anger out on her children, especially her daughters. Though she did treat the boys better, they didn’t have a mother figure they could look up to. Orton’s father had no ambitions and earned very little, he is described as a totally submissive man and was not respected by either of his two sons. The harsh landscape of Orton’s early upbringing and his parents’ marriage which was from all accounts miserable, can be seen in his plays. But Orton also manages to turn some of the most terrible events into scenes of boundless humour, which was one his greatest gifts.

Here I’ll take a quick look at two of Orton’s plays.

Entertaining Mr Sloane

This was adapted into a film in starring Peter McEnery and Beryl Bainbridge in 1970

This was adapted into a film in starring Peter McEnery and Beryl Bainbridge in 1970

Kath. You have the air of lost wealth.

Sloane. That’s remarkable. My parents, I believe, were extremely wealthy people.

Kath. Did Dr Barnardo give you a bad time?

Sloane. No. It was the lack of privacy I found most trying.

Orton’s sister Leonie has stated that the character Kathy in Entertaining Mr Sloane is based on their mother Elsie.

Kathy lives with her elderly father, an old man called Dadda that knows Sloane, the man that comes to rent a room at their house, is a murderer and psychopath. Kathy, clingy devious and manipulative, allows the young handsome man who comes with a tale of orphanages and vulnerability into her home, obviously attracted to him. The house is strategically positioned on a rubbish dump. The environment Orton sets this play is important, it reveals many aspects of all the characters personalities, and one could say that they are suited to the position of the house by the end of the play.

Kathy talks as someone who believes she is middle class with exaggerated airs and graces, a pretence of refinement. Her sentences are constructed in a way that Kathy believes the middle classes must talk. Yet, there is something artificial about the sentences, even fantastical. They often come across as both awkward and hilarious. Words that may have been fashioned from advertisements or television.

Kathy talks as someone who believes she is middle class with exaggerated airs and graces, a pretence of refinement. Her sentences are constructed in a way that Kathy believes the middle classes must talk. Yet, there is something artificial about the sentences, even fantastical. They often come across as both awkward and hilarious. Words that may have been fashioned from advertisements or television.

Kath, in her forties, is living on top of filth. One cannot even imagine the stench of the rubbish dump for the residents of the house. The social classes are very much a theme in Entertaining Mr Sloane, people are disguising their obvious poor status in life and pretending to be something completely different.

All the characters in Entertaining Mr Sloane are playing constant power games in their dialogue. Sloane uses his body and sexual prowess to dupe both Kathy and her brother Ed and use them to his advantage. Sloane, Kath and her brother Ed are a triangle of sexual desire and possession. Both Kathy and her brother Ed are sexually attracted to him. His youth and looks give him power over the situation, especially over these two middle-aged characters, who he constantly manipulates. It’s obvious Sloane he has no plans to stay in this house, he is a person that moves from place to place surviving in a very parasitic way off other people. He has no emotions and has no feelings of guilt or even worry. He believes that he is in control of events at the house. However, though a psychopath and killer, Sloane has no idea he has met two completely savage characters with no morals, who are totally self-serving to extremes. The brother and sister will soon trap Sloane in the house forever. Keeping him like a sexual toy to play. He will be at their mercy. By the end of the play they are organising how to share Sloane as if he is a mere object. It’s a brutal picture of humanity, though the dialogue and plot are so outrageous and fantastical, you cannot help but laugh at many parts of the play. This is also a savage depiction of sexual desire and ownership, how human beings like to own people and control them. None of the characters in the play is likeable, none have any redeeming features. Yet by the end, you feel more for the psychopath Sloane then either Kath or her brother Ed.

The Good and faithful Servant

Orton’s sister Leonie states that Buchanan is based on Orton’s father

This play is about the lost life and the lost opportunities of a submissive unremarkable man who plods through his life, experiencing very little and unable to make real decisions.

Buchanan almost acts like a robot, simply existing for the trivial job that pays a meagre wage. He sacrificially submits to his low station in life, to the mundane and an office run like a machine as if he had no other choice. Buchanan is one of the longest-serving employees, having worked at the company for fifty years. Buchannan has never tried to fight what appears to be non-existence in society, performing year after year without argument. Orton creates a character that seems almost soulless.

The play begins with his retirement. He is going to feature in the company’s magazine. In the first scene, he meets a cleaner, a woman who has also worked at the company for fifty years. He tells her that he feels he knows her and that she reminds him of the ‘only woman he ever loved’. It turns out that she is, in fact, a woman he had met and had a brief physical encounter with many years earlier. Hilariously, neither met at the company during the fifty years they worked as they entered the building through different doors. In the retirement club Buchannan finds that no one recalls him working at the company, he has been invisible to everyone. The company is described as having many doors, and employees going through one door may never meet another colleague for years.

Orton paints a grim picture of a society where some working-class employees are doomed to being nothing more than robots to pay their way in life. But he also shows that human beings themselves can submit to the lowest role in life without a fight. As if it’s a genetic component passed through the generations creating people that never look above their station.

It’s a wonderful play, incredibly funny but utterly sad, it’s that mixture of emotion that makes it Ortonesque.